|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

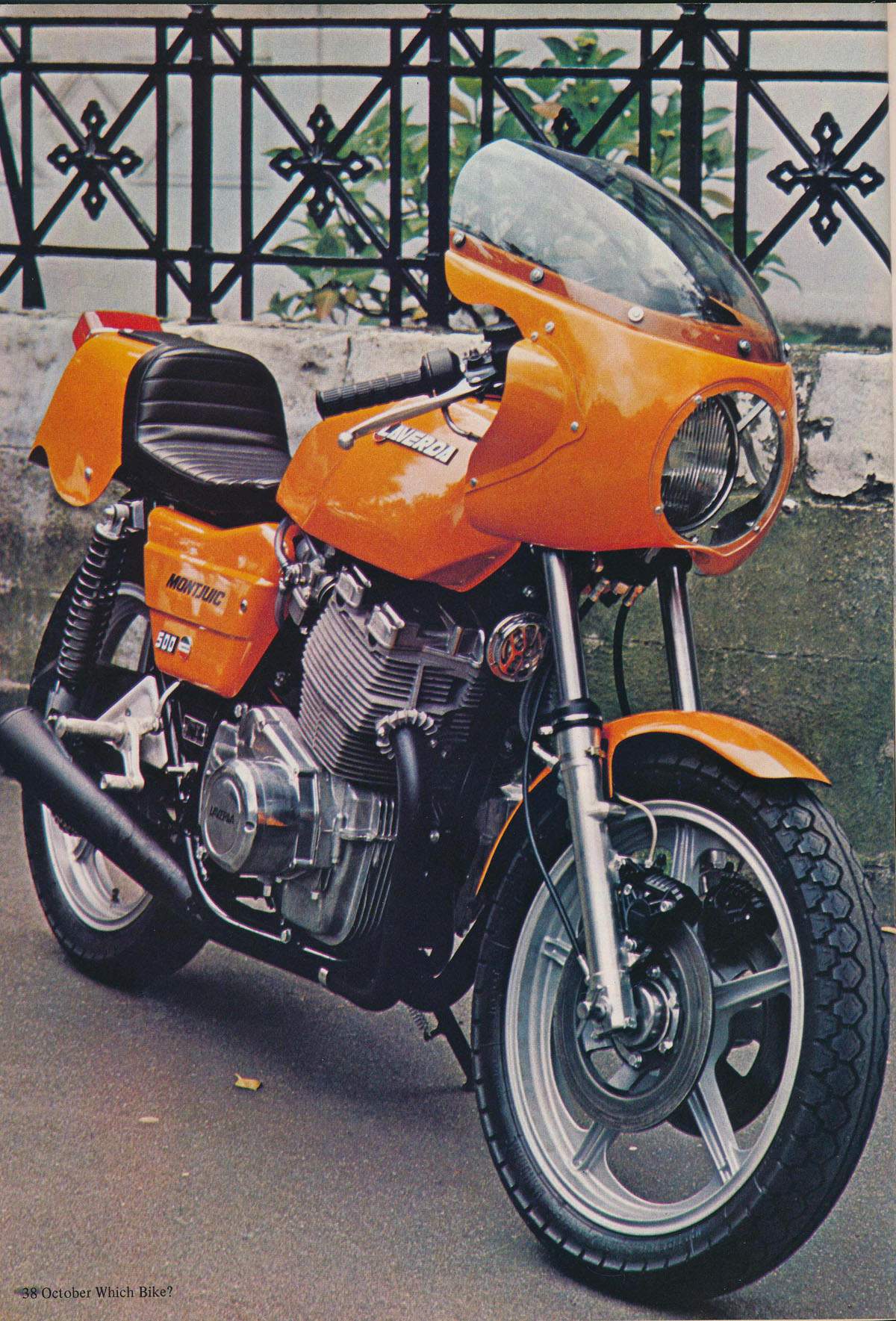

Laverda Montjuic Mk I

The Montjuic name ranks alongside other legendary bikes in the story of Laverda twin and triples, such as 750SFC and Jota. With its Café racer looks and bright orange paint job, the Montjuic looked like a scaled-down 750SFC, and an enlarged version of the final Ducati Desmo single. Both were bikes with a special place in the hearts and minds of sportsbike enthusiasts. As with the Jota, it was Roger Slater who was instrumental in the creation of the Montjuic. Heavily involved in production racing at the time, Slater had a natural ability to sniff out a marketable product. He had imported a Formula 500 and, realizing that it would not be a viable competitive racer in British events, he decided to use it as the basis for a middleweight Laverda twin that he (correctly) believed British enthusiasts would want to own. He must also have realized by then that the Alpino was never going to make the grade, hampered by a combination of lacklustre styling and a high price tag. The Montjuic was named after the famous parkland road circuit in the heart of Barcelona, where Laverda had often enjoyed success. It was essentially a Formula 500 for the street, refined just enough to be legal under the British Road Traffic Act. Its styling was gorgeous, as was the bark from its two-into-one matt-black exhaust system — note that there is no mention of the word 'silencer'! The Montjuic looked as though it was speeding even when it was standing still, and it was impossible to ignore. It grabbed sales in a way that the less adventurous and far more sober Alpino had never been able. Using the standard Alpino tank, Slater commissioned Birmingham-based Screen and Plastics to manufacture a batch of suitable handlebar fairings and hump-back single saddles, together with more sporting mudguards, Jota-type bars posed as clip-ons and rear set foot controls; the latter were mounted on triangular alloy plates. One of the major problems that beset the first-series Montjuic machines was that the fairing was fork-mounted and caused weaving at high speed. This was largely rectified on later machines (series 2), which employed a frame-mounted fairing designed by the Italian Motoplast concern, but manufactured in Britain. Of course, a really critical rider could find much that was wrong with the Montjuic in comparison with other five-hundred twins of the same era - Moto Guzzi V50, Ducati Pantah, Yamaha XS500, Honda CX500 or even the Morini 500. All of these were relatively civilized, quieter and, in most cases, faster too. However none of them had the same sort of character, none were so compact and none enjoyed quite the same sort of relationship with its rider. The Laverda was far from ideal for any form of commuting or touring, but for pure enjoyment, fast road work or even a touch of club racing, or 'track days', in 1980 no half-litre machine could compare with the Montjuic. Its nearest rival was probably the 350 LC Yamaha water-cooled two-stroke twin, which was very slightly larger and heavier than the Montjuic. Both gave the feel of a 250cc, and, as I found out one day at Snetterton in summer 1984, virtually identical on lap times. The Yamaha twin was a shade quicker, but the Laverda made up lost ground on the corners and braking areas. The 'Monty', as it became known, soon had me hooked. By the time I got to ride one, production had long since ceased; otherwise I might well have gone out and bought one! Source Mick Walker Overview Montjuic

In addition to the simple mechanical alterations, the Montjuic’s cafe racer

credentials were complimented with attractive seat and fairings manufactured out

of GRP, a set of ‘Jota’ bars and some elegant cast aluminium rearsets. The

bodywork was manufactured in the UK by ‘Screen and Plastics’ . Bikes were

shipped from Italy sans seat unit and fairing and these items were retro-fitted

by Slaters. Unusually, the fairings and seats were finished in self colour gel

coat rather than painted, something I found quite surprising when I acquired my

un-restored l MK II. Such is the quality of the Screen and Plastics bodywork

that I always assumed all Montjuics had a painted finish.

KAWASAKI

Z500 BENELU504SPORT LAVERDA 500MONTJUIC No longer are the middleweight bikes the low-life alternatives to the last decade's expansion into the litre-plus arena of high-performance machinery. John Nutting tests three five-hundreds which for reasons of price, performance or appearance (or all three together) offer the discerning motorcyclist everything that could possibly be wanted in a machine. Photography by John Perkins and Ian Dobbie. It's not so long ago that Kawasaki owners were the constant butt

of every joke under the sun about poor handling. But that's all changed with the

introduction of the company's smallest multi-cylinder four-stroke, the Z500. But if you think that the littlest four is just the six-fifty with all the major dimensions reduced then take a closer look. And find out the subtle details in the development of a sporting roadster for the eighties. True, the concept of the Z500 follows the theme found in most of the top-selling Japanese motorcycles of the last few years — an across-the-frame in-line four-cylinder engine mounted in a duplex-cradle chassis. In fact, on paper you'd be hard pushed to detect the major differences between the 497cc Kawasaki and the first of the smaller fours, Honda's CB500, introduced in late 1971. Both have similar power outputs, compression ratios, carburettor sizes, overall dimensions and dry weights. But the closer look reveals the ways in which the motorcycle buyer has become more demanding in the intervening eight years. And a brisk ride down a twisty lane is even more eye-opening. The Z500 is an extremely compact machine with a wheelbase of just under 55 inches and a dry weight of 4231b. It feels small, thanks mainly to a narrow 3.3 gallon fuel tank and tidy proportions around the side panels and footrests that allow the rider to place both feet flat on the ground at traffic stops. The frame itself appears conventional in that it has a large diameter backbone supporting the steering head. But it is substantially supported above the engine with massive gusset plates which effectively stiffen the front end of the structure. The front fork, a smaller version of the unit found on the shaft drive Z1000, appears also to be overly strong with leading-axle sliders with big clamps for the front-wheel spindle. At the rear, the swinging arm pivots on four needle roller bearings. The torsional stiffness of the front fork is a real necessity

when over seven inches of travel have been opted for along with a steep steering

head angle of 64 degrees. Some riders might argue that the suspension is harsh, and that's

certainly true although it's not because of the spring rates. Kawasaki have

opted for an average 50 lb/in fork spring rate with minimal preload along with

ideal 901b/in rear springs. Fortunately, nothing is lost in the overall handling. The steering is excellent, being neutral and light to control whether the bike is being weaved through dense traffic or carved through tight bends. The tyres used impart confidence, being a ribbed Dunlop Gold Seal front matched with a Japanese-made TT100 at the rear, though we'd doubt if these would be much good when raced, in which role the Kawasaki most certainly will find itself. Moreover, the Z500 feels much more stable when cranked over than the CB500 ever did. And when matched to the sintered-pad disc brakes now found on all the top Kawasakis, you have a chassis package that marks a new high for Japan. Two thin 10.8 inch diameter discs are used at the front with floating calipers while the rear unit uses the same disc but with a double piston caliper. Only criticism is of the excessive reach to the front brake handlebar lever. In performance, the Z500's engine matches the chassis perfectly. Peaking at a claimed 52bhp at 9,000 rpm with the red line marked at 9,500 rpm, it easily urges the bike to almost 1 lOmph flat out and puts indicated cruising speeds of around 90mph comfortably in the grasp of the rider even when there's only small sections of open road to play with. Much of the engine's excellent power is derived from the use of double overhead camshafts and the four free-breathing 22mm-choke Tekei carburettors. Like the Z650 and the old CB500, the four-throw crank runs in plain bearings and drive is through a Morse-type chain and gears to the wet clutch. Bore and stroke are the same as the Z250; 55 x 52.4 mm. But new is the use of another Morse-type chain with an automatic adjuster for driving the camshafts. Some of the surprising snap throttle response and startling acceleration is derived from the six-speed gearbox and wide ratios. Gear change action is slick and noiseless and the 'box retains the useful neutral-finding dodge that stops you selecting second from bottom at a standstill. Kawasaki appear to have selected the gear ratios with drag racing in mind for the reve drops between gears are as similar all the way through the range instead of having a large gap between bottom and second and closing up the other ratios. In normal use though the engine is so flexible, pulling cleanly and usefully from as low as 1,000 rpm in top, that the lower ratios hardly ever get used. At the test strip though the effect is obvious. The Z500 fires

like a cannon from the gate to be easily the quickest-accelerating 500cc machine

on the market getting to 60 mph in 6.5 seconds. With no kickstart lever, it's just as well the self starter was

reliable. The engine fires up cleanly and is helped on cold mornings by the

throttle-valve lifter incorporated into the choke mechanism. The clutch was

annoying though. Like an old Triumph, it would stick after being left overnight. One thing is sure with the Benelli 504 Sport; you could never

mistake its intentions. It looks a sporting machine and in every facet of its

character it acts like one. Which is a blessing for Benelli. But the 504 Sport displays style and flashiness rarely, if ever, found in Jap bikes. Finish is in a metallic black paint set off by striking gold cast-alloy wheels and a small Guzzi Le Mans. And it's a small bike that begs to be ridden fast. The power

band is sharp and needs to be nursed along on the five-speed gearbox. And it's

not until you're cruising above an indicated 80mph that the riding position

feels at all comfortable. On top of that the bike feels sluggish unless you wring its

neck, compared to the other two machines featured here. In fact, the Benelli is

barely slower than the Kawasaki in a flat-out dash, mainly because of the

wind-cheating riding position, with a top speed of around 108 mph. (We saw 115

mph once on a long downhill section of road.) Once into its best area, that is, when the rev meter is hovering

in the 6,000 to 9,000 region, the 504 perks up appreciably and the real meaning

of Italian motorcycling rings true. There are few changes to the 504 to bring its power from the 47bhp of the 500LS to a sportier 49bhp at 8,900 rpm. Bore and stroke remain the same at 56 x 50.6mm, though the pistons pump the compression up to 10.2 to 1 and the camshaft has more lift and overlap. Gearing is the same as the LS giving 5,900 rpm at 70mph. Apart from the use of alloy wheels and the interesting adoption of the Moto Guzzi linked braking system, there are few changes to the chassis either. At speed the bike feels taut and stable thanks to a shallow steering head angle and a low centre of gravity. But the suspension is mismatched and that same front end geometry leads to a measure of resistance when you're hauling the bike from lock to lock at speed through the twisty bits. The front fork is under-damped, leading to some choppiness over bumps, a feature that is in conflict with the rear suspension which is undeniably hard. It could well do without this as the seat is similarly rock-like. Not that this necessarily detracts from the enjoyment of the

Benelli. The four-into-two exhaust emits a jubilant growl and the hand controls

are slick and easy to use. Also there was much too much engine vibration getting through to

the rider's feet. And neither was the bike very economical with only 46.3 mpg

overall. How do you transform an ordinary motorcycle into a popular

classic? Perhaps you refine it over a number of years to make it appeal to the

widest possible number of potential buyers. The proof? The Laverda Montjuic has been outselling the standard 500cc Alpino by three to one. And this is despite the race-replica being the most expensive 500 on the market at a shocking £2,095. But such is the appeal of a super-sporting machine with a proven

record in competition. And Laverda were always aware of it since the lamented

demise of the SFC, the production racer based on the factory's now obsolete

750cc SF twin. The British Laverda importers have always adopted a more cavalier approach. And no sooner did they prove the reliability of the basic eight-valve double overhead camshaft Alpino unit by pulling off an impressive one-two in the 500cc class in the 1978 Barcelona 24-hour race at Montjuic Park than they realised that they were onto a winner in the home market. Furthermore they also realised that if they could offer a high performance 500cc machine in road trim, it would qualify for the tight production racing regulations currently enforced in UK meetings and beat the Yamahas previously dominating the class. They were right and the Montjuic sales have boomed. Competition record apart though it's not difficult once you've

ridden a Montjuic, to realise why the bike's so appealing. It's got the

purposefulness of a BSA Gold Star and the style of the old SFC, which

incidentally it can outperform comfortably. The frame is stock and retains the same Marzocchi suspension front and rear. The basic engine and six-speed transmission are unaltered too. However, the pistons give a compression ratio of 10.2 to 1 and the camshafts have revised timing with the effect that the compression pressure is upped to 150 psi from 115 psi. To cope with this the 32 mm choke downdraft Dellorto carburettors are recalibrated and the air cleaner is dispensed with while a megaphone-type extractor exhaust system to suit the cams also gives extra cornering clearance. The extra cranking pressure has had its effect and though the

electric starter motor is retained and normally copes with its job well, the

battery is soon to be uprated to make it foolproof. Few would argue with that since owners have been complaining that they are running over the factory-stipulated rev limit of 9,500 rpm in top gear with the stock gearing of a 42 tooth rear sprocket - which gives 116 mph. Given the use of a 40-tooth sprocket the 125 mph that Slater claims for his bikes should easily be in reach. After all, with a 38 tooth sprocket in the Island this year their own bike was clocked at 129 mph through the Highlander and the 9,600 rpm that Peter Davies saw on the rev counter compares with the computed figures. What's more the bike went to 10,300 rpm on the drop to Brandish. That's 139 mph. . . In day-to-day use such heady performance figures are neither

here nor there. And anyway there's little chance of proving them since Slater

invariably uses the demo Montjuic as a spare for racing. Laverdas have always been favoured for their good handling but

the Montjuic Though we weren't able to test the decibel level it must break

the limit quite easily. Complementing the performance the handling and suspension are tight and taut as you might expect of a machine that has been trimmed down to about 350 lb dry without changing the spring rates. And for the same reason the three Brembo disc brakes have no trouble in hauling up the lightweight bike from speed. Neither is the machine finicky. John Owen Reckons he has been

getting 55 mpg in the 2,000 enjoyable miles he's run the machine.

|

|

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |